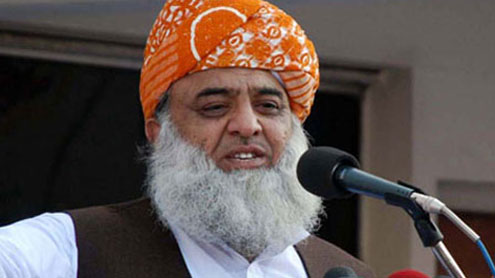

Judging by the hero’s welcome given to Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan in his just-completed tour of the Arab world, it’s not surprising that, once again, Turkey is being held up as “the best model for change” across the region.Those boosting Turkey’s standing include not merely Erdogan and the country’s increasingly bold leadership, but equally political commentators across the Arab world (and indeed, around the globe), and millions of Arabs hoping to establish truly democratic societies in the wake of the Arab revolutions.

Judging by the hero’s welcome given to Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan in his just-completed tour of the Arab world, it’s not surprising that, once again, Turkey is being held up as “the best model for change” across the region.Those boosting Turkey’s standing include not merely Erdogan and the country’s increasingly bold leadership, but equally political commentators across the Arab world (and indeed, around the globe), and millions of Arabs hoping to establish truly democratic societies in the wake of the Arab revolutions.

There is no doubt that the Turkey of 2011 is a remarkable success story in many areas, particularly compared with the political, economic and cultural state of the country less than a generation ago.But is the country really a model for Arab pro-democracy revolutionaries to look to, as they struggle to establish democratic political systems in the ashes of decades of dictatorship, amid political and economic marginalisation? Let’s look at the record.

Democracy – less than meets the eye

At first glance, Turkey has become a model of democracy and pluralism, and is serving as a beacon for other Islamically oriented parties looking to participate in their emerging political systems. Culturally speaking, the country is, ostensibly, an equally inspiring model: Istanbul is one of the world’s most vibrant and open cities, while the country’s long Mediterranean coastline remains largely a (thankfully) undiscovered hybrid of local and cosmopolitan cultures.

Turkey has had several substantially free and fair elections and a national referendum in the past decade, which have seen one party – the Justice and Development Party (AKP) – achieve and maintain power, and substantively change the country’s constitution, all against the wishes of the previously all-powerful military. Just as importantly, the AKP is not trying to stamp out criticism by its rivals; last year’s constitutional referendum saw particularly intense debate, with Istanbul and other cities festooned with posters freely comparing Erdogan to Hitler.

Yet a slightly deeper look at Turkey’s record on political democracy, an examination that moves beyond the usual focus on elections, reveals a country that still has a long way to go before it can be considered fully “free”.The Economic Intelligence Unit scores Turkey 89th of 167 countries, which puts it well below the former Sovet Bloc countries of Eastern Europe, or African success stories such as Mali and Ghana – and only a few steps above Palestine and Venezuela. Freedom House’s latest report scores Turkey at only a three out of seven on both political rights and civil liberties, giving it a rating of “partly free”.

A core problem continues to be the large gender gap in political participation, which Turkey ranked 126 out of 134 countries by the Economic Forum in its 2010 Global Gender Gap Index. Given the problems with women’s empowerment in the Arab world, this should be of serious concern to anyone looking to copy the Turkish model.As important, corruption continues to plague the Turkish political system and economy, and is closely tied to the ongoing restrictions on political parties, on civilian oversight of the military, and press freedoms that belie claims to be a well-functioning democratic system.The Economic Intelligence Unit scores Turkey 89th of 167 countries, which puts it well below the former Sovet Bloc countries of Eastern Europe, or African success stories such as Mali and Ghana – and only a few steps above Palestine and Venezuela. Freedom House’s latest report scores Turkey at only a three out of seven on both political rights and civil liberties, giving it a rating of “partly free”.

A core problem continues to be the large gender gap in political participation, which Turkey ranked 126 out of 134 countries by the Economic Forum in its 2010 Global Gender Gap Index. Given the problems with women’s empowerment in the Arab world, this should be of serious concern to anyone looking to copy the Turkish model.As important, corruption continues to plague the Turkish political system and economy, and is closely tied to the ongoing restrictions on political parties, on civilian oversight of the military, and press freedoms that belie claims to be a well-functioning democratic system.

An economic miracle that is hard to share

At the heart of Turkey’s rise to becoming a regional powerhouse and a role model has been the rapid development of the country’s economy during the past fifteen years or more. Today Turkey stands with Brazil atop the list of developing countries in the levels of development and growth of its economy.Annual growth jumped from just over two per cent in the 1990s to well over eight per cent in the mid-2000s, as did worker productivity in the all-important manufacturing sector. The country’s growing foreign trade, a position that rivals Egypt and other Arab countries, can only be viewed with envy, as does its low budget deficits and even surpluses it boasts.

However enticing, there are several reasons why the Turkish “miracle” will be hard to emulate across the Arab world.First, the present dynamic emerged in good measure out of a severe banking crisis early in the decade, which saw the imposition of a reform plan that helped stabilise the financial sector, allowing it to weather the storm of the past few years, while banks in Europe and the US have faltered.Second, the economy was liberalised in many ways from within, rather than neoliberalised from outside.

The rise of the AKP and the period of rapid growth corresponds with the rise of a class of “Muslim” entrepreneurs, symbolised by MUSIAD, or Independent Industrialists and Businessmen’s Association, which helped challenge the previously dominant TUSIAD, or the Turkish Industry and Business association. The latter was long tied to the state-dominated economy, which was riveted by corruption, cronyism, and a lack of farsighted economic leadership.

Beginning with the rule of Prime Minister Turgut Ozal in the 1980s, Turkey opened up as much, if not more, from within than as a result of foreign-imposed structural adjustment. These changes were part of a larger project of wresting control of the economy from the military-dominated state by the country’s once proud, but long-suffering, entrepreneurial class.In contrast, externally imposed structural adjustment reforms that are the norm in the developing world usually have no roots in the local economy, and thus benefit only a small section of the country’s population.

This economic plan allowed Turkey to chart its own path towards indigenous-generated and locally controlled growth, something most post-revolutionary Arab countries (with the exception of Libya and its huge petroleum reserves) will have a hard time copying, given their much weaker position vis-a-vis the global financial system – a key, if largely unstated, element of the “system” of which “the people” have “wanted the downfall” in this revolutionary year.

Moreover, the Turkish “miracle” would not have happened without a strong bit of historical and geographical good luck: Turkey’s opening accelerated in the wake of the disintegration of the Soviet Union, out of which emerged a group of Central Asian states with strong historical, cultural and linguistic ties to Turkey. As important, many of them were sitting on huge petroleum reserves. The sudden creation of huge potential market right next door to Turkey, with countries with whom it has centuries worth of economic and cultural links, is a situation no Arab country, whether in North Africa, the horn of Africa, or the Levant, can hope to match.Although African and Levantine economies have significant potential for development, at this time they are simply not poised to provide markets for Egypt, Tunisia, or Syria – to take three examples – of the kind that Central Asia has provided to Turkey.

Because of this, much needed economic growth in the Arab world will depend on a combination of greater trade with a weakened Europe and the developing of myriad more creative, smaller-scale economic relations with surrounding countries that won’t provide the same quick jolt that Turkey’s Central Asia neighbours provided it with at the start of its growth spurt.It will also mean small producers, manufacturers and traders operating with a level of independence that the country’s elites would likely not support, since they could not control operations – and in so doing siphon off some of the wealth such relations generate. – Aljazeera